A Tailored Intensive

Vocabulary Trainer Using an Online Flashcard Site

Yoneoka, Judy (Kumamoto Gakuen University)

Key

Words: Learner

autonomy, Flashcards, Vocabulary learning, short-term memory, long-term memory

1. Introduction

Flashcards[i]

have been a standard foreign language vocabulary aid most likely from the

beginning of the invention of paper.

Based on developments in the past century in cognitive memory research,

however, flashcards have been developed into mechanized and systematic

vocabulary tools by B.F. Skinner and later by Sebastian Leitner (1972). With

the advent of computers, flashcards programs such as Lernkartei for German and

ALICE for Spanish appeared. Further developments in computer technology have

led to the flashcard system going online in various forms (freeware, shareware,

opensource, java) and on several sites, both commercial (MemoryLifter,

Flashcard Station, etc.) and non-commericial (Mentalcode, VocusPocus,

Studystack, etc.). Cellphone and PDA versions have also recently begun to

appear.

The

Leitner system (also called the “box system”), although in general use in

various flashcard systems on the Net, is relatively unfamiliar in ESL and

vocabulary circles. This is perhaps because flashcard systems in general are

often dismissed as ineffective in contrast to more sophisticated vocabulary

acquisition methods such as learning vocabulary in context or within semantic

fields. In the light of research on learner styles and autonomy, however,

flashcards offer a viable option for learners with the appropriate skills,

preferences, and motivation.

This

research will begin with an overview of the flashcard debate and discuss how

the Leitner system enhances the effectiveness of flashcard study. It will

proceed to explain a similar flashcard study system developed by the author and

document a two-month experiment in studying Korean online using this system.

Finally, it will be showed how online and offline flashcard resources can be

combined with the study system to provide a well-rounded vocabulary study

program for ESL university students.

1.1 The Flashcard Debate

An online discussion on

flashcards at how-to-learn-any-language.com/ reveals several differences in

opinion regarding their usefulness:

*Flash cards are easily the best vocabulary

tool out there... I'm a strict adherent to one-word-a-card … and it's worked so

far.

*No offence, but I disagree with you

completely. I don't think you can beat reading, reading and even more reading

for picking up vocabulary. …. I find them to be too much like a "phone

book" list of words and that's artificial for me.

*I'd agree with you that flash cards, per se,

don't necessarily have anything over general reading. However, when combined

with programmed spaced repetition via a Leitner-style box system (software or

hardware), they are an extremely effective method of learning and most

importantly retaining vocabulary.

*I've never been a big fan of flashcards … but

I am learning to appreciate them for their portability…Will the words be as

natural as if I'd encountered them in reading or listening? No. But it's better

than not reviewing or encountering them at all.

*For me I have had good luck with short term

retention with flashcards (for exams for example), but for long term retention

reading in my target language has really been the best. … I just find

flashcards very tedious and I don't think you can learn anything from something

you find tedious. Others find them very helpful and I think that's great,

whatever works!

The

discussion here brings up several strengths (portability, systematicity, effectiveness for

learning) and weaknesses (artificiality, lack of context, tediousness) of

flashcards in contrast to reading. To these could be added the advantages of

learner choice and autonomy and the disadvantage of having to spend time to

create cards (although perhaps can be included in the interpretation of “tedious”).

Another advantage for some learners is the quiz-like nature of the activity

itself. In general, we can say that flashcards lend themselves more to those

who enjoy puzzles and games than to those who would rather curl up with a good

book..

The

necessity of a spaced repetition component (also called “graduated interval

recall”) to ensure the effectiveness of flashcards for long-term retention is

also mentioned in the discussion. Spaced repetition means that a specific review

schedule is set and used by the learner to repeat stacks of cards at certain

intervals to ensure that the vocabulary learned is still in the long-term

memory. This component is often overlooked by occasional flashcard users, but

crucial to success with flashcards. It is an integral part of many online

flashcard systems and software, most of which are based on the Leitner box

system. Section 2 reviews the Leitner system briefly, and contrasts it with a

similar system developed by the author.

2. The

Leitner System: A Brief Review

The

Leitner box system (German psychologist Sebastian

Leitner) is a method for learning and retaining vocabulary in both short-term

and long-term memory. In its low-tech version, an actual box with several

compartments is used to organize flashcards in terms of relative retention in

the user’s memory. When cards from a certain box are reviewed, those that were

remembered are promoted to the next box, whereas those that were forgotten are

sent back to the first box. Thus, not only are cards reviewed systematically,

but those that are more problematic for the learner are reviewed more often. A

specific review schedule is set and adhered to, providing the spaced repetition

component described above.

Online

versions of the Leitner system provide both the flashcards and the

compartments, and promote or demote those cards automatically. The commercial

cite MemoryLifter, for example, explains the algorithm used in their system as

follows (2004, online):

- Initially, all cards are derived from the Pool,

which contains all cards available.

- Check whether any of the boxes are full. If so, ask

for a card from that box. If none of the boxes are full, place a new card

from the pool in the first box and ask it.

- If the card is answered correctly, promote it to the

next box; otherwise, demote it to box 1.

- When placing a card in a box, put it at the end.

When asking a card from the box, ask in the order it was placed in the box

(first in - first out principle).

- Continue with step 2 - 4 until done.

On

some Leitner-based online systems, the spaced repetition intervals are preset.[ii]

On Flashcard Exchange (2004, online) for example, “an e-mail is sent when it is time to review a cardfile again. The

default review periods are based on the number of times you have successfully

completed a cardfile.” After the first completion of a set, the next review is

four days later, after the second completion it is seven days later, etc. Another characteristic of the Leiter-based system is that it

concentrates on receptive retention of the target word, and does not

specifically require production. Cards can be flipped to test production, of

course, but this is generally treated only as an optional side step in the

learning system. This means that practice of writing, a crucial part of

learning a language with a different writing system such as Chinese, Japanese

or Korean for English speakers, may tend to be overlooked.

This

difficulty is solved in a similar system developed independently by the author

in the 1970s to study Japanese (hereafter referred to as the JY method) using

homemade kanji cards, and adapted to the paid system available on www.flashcardexchange.com to study

Korean in 2006. In the JY method, the study schedule is set by the day, fixing

an intuitively easy-to-follow review plan. Cards are promoted weekly from the

Pool, first into a reading stack and then into a writing stack. Missed cards

are not demoted, but stay in the same stack. Promoted cards are replaced by new

cards from the Pool so that the reading stack retains a set number of cards

(20-25 were used when the author studied Japanese, 50-100 in the online Korean

version). Each stack is labeled with a day of the week, on which they are to be

reviewed.

Figure

1 demonstrates the first three weeks of the JY weekly repetition flashcard

method. In the first week, only reading stacks are studied, but both reading

and writing stacks are ready for study from the second week. In the figure,

after testing the daily reading cards, a total of 45 cards were recalled

correctly after one week, and graduated from the reading files to newly-formed

writing files. New cards were added to keep the number in each reading stack at

20.

|

|

Monday |

Tuesday |

Wednesday |

Thursday |

Friday |

Saturday |

Sunday |

|

WEEK 1 |

READ (20) |

READ (20) |

READ (20) |

READ (20) |

READ (20) |

READ (20) |

READ (20) |

|

140 cards studied |

|||||||

|

WEEK 2 |

READ (20) |

READ (20) |

READ (20) |

READ (20) |

READ (20) |

READ (20) |

READ (20) |

|

140 cards |

↓ 5 |

↓7 |

↓8 |

↓3 |

↓6 |

↓12 |

↓4 |

|

45 cards |

WRITE (5) |

WRITE (7) |

WRITE (8) |

WRITE (3) |

WRITE (6) |

WRITE (12) |

WRITE (4) |

|

195 cards studied (45 new cards introduced

from pool) |

|||||||

|

WEEK 3- |

READ (20) |

READ (20) |

READ (20) |

READ (20) |

READ (20) |

READ (20) |

READ (20) |

|

140 cards |

↓ 4 |

↓ 5 |

↓ 3 |

↓ 9 |

↓ 6 |

↓ 8 |

↓ 3 |

|

+83cards |

WRITE (9) |

WRITE (12) |

WRITE (11) |

WRITE (12) |

WRITE (12) |

WRITE (20) |

WRITE (7) |

|

223 cards |

↓ -2 |

↓-4 |

↓-3 |

↓-3 |

↓ -1 |

↓-7 |

↓-1 |

|

- 20 cards |

DONE (2) |

DONE (4) |

DONE (3) |

DONE (3) |

DONE (1) |

DONE (7) |

DONE (1) |

|

203 cards studied (83 new cards introduced

from the pool, 20 cards completed) |

|||||||

Figure 1. The JY Weekly Repetition Flashcard Method

Although the actual number of cards reviewed and remembered each

day will vary, personal experience has shown that one to two practice sessions

each day results in approximately 1/4 of the cards being recalled the next

week. This means that of the 140 cards studied weekly in Figure 1,

approximately 35 cards will “graduate” into the writing and done files

respectively. That is, from the third week approximately 35 new words can be

consistently expected to be acquired each week. Each card takes at least 3

weeks to progress to the done stack, but can take as long as needed to be

acquired. Especially difficult-to-remember cards have been known to linger in a

stack for several months or more!

The

choice of whether and when to review the “done” cards is up to the learner, but

should probably take place whenever a done stack reaches a certain number (say

20 or more) of cards. Cards that were not remembered should go back into the

pool to restart the process.

3. A pilot

experiment in Korean vocabulary acquisition using the JY method with www.flashcardexchange.com

Flashcard

exchange (hereafter referred to FE) is an online flashcard database with over

4,000,000 user-created flashcards available for anyone to study. The ability to

create, use and review flashcards is free for all users, but the compartment

function, which allows for subdivisions or compartments within flashcard files,

is only available to paying members (a one-time $19.95 fee). The addition of

compartments allows for a Leitner-type review system, which is built into the

fee-based program and available for paying users.

In

order to adapt the JY weekly repetition method for use with this site, the

built-in review schedule was not used.

Rather, files were named by the day of the week (e.g. Monread, Wedwrite,

etc.). Each file was created with three compartments. The first compartment

holds the cards to be tested; the third compartment houses cards that were

previously promoted. The second compartment serves two functions: (1) when

testing cards, it serves as a holding place for cards that have been remembered

until they can be copied and pasted into the corresponding writefile and

promoted up to the third compartment, and (2) when studying cards, it is a

temporary holder for those cards that have successfully been processed in the

learner’s short term memory. These are then demoted to the first compartment

after the day’s study is complete.

This

modified system was used to study Korean vocabulary over a period of 2 months,

from 2/28 to 4/30/2006. Two reading files (50-100 words each) and one writing

file were studied daily. The words to be studied were arranged in 50-word

subfiles[iii]

from two sources on FE: (1) a file of 739 low intermediate level words created

by bair787, and (2) an advanced file of 2316 words recreated by the author (the

original file by another author has since been deleted). Thus approximately

3055 words in 62 50-word sets were prepared for study.

The

first week began with 700 words, i.e. 100 words in 2 50-word read files per

day. From the second week, when a file fell below 50 words, a new file of 50

more words was added.[iv]

Study sessions lasted approximately an hour, and were repeated during the day

if desired (usually no more than once). By the end of the two months, another

1439 words had been introduced into the system, at a rate of approximately 24

new words a day (=1 new file every two days) Of the total 2139 words in the

system, 1124 had advanced to the writing file at the end of two months, and 672

of these had graduated out of the system entirely. This indicates that over

half of the words had been retained in long-term memory for a week at least

once, averaging out to approximately 19 words per day.

It

must be noted that the author had previous experience studying Korean and was

already familiar with approximately 250 of the words on the low intermediate

list, although had never written them. This number is approximately 37% of the

672 graduated words. Assuming that these previously known words were all among

the “graduates”, however, still leaves 672-250= 422 new words acquired in

writing and 1124-250=874 in reading. Of the 19 words per day mentioned above, 5

of these would have corresponded to words previously known.

To

test retention, approximately half of the 672 graduated words were tested again

at random 45 days later. Retention rate was found to be approximately 80%.

Adjusting this to account for the previously-known words mentioned above (assuming

again that all previously known words had already been graduated and were being

retained at 100% rate), the retention rate for newly acquired words worked out

to approximately 64% after 1 1/2 months.

4. Adapting and supplementing Flashcard Exchange for ESL students

As mentioned in the

introduction, appropriate skills, preferences and motivation are prerequisite

for success with flashcards. Thus it may not be suitable for in-class work with

a variety of students. However, if introduced and offered as a study tool, it

could well be used by students who have time, facilities (i.e. a computer

available) and self-motivation. It is recommended that the student make use of

the compartments by paying the one-time fee, but a suitable substitute for

compartments can be created on the site by making and renaming files combined

with much copying and pasting.

It

is suggested that students begin with the 2235-word General Service List, which

is available on the FE site with Japanese translations. For university

students, however, most of this list should be already known. More advanced

students can try the 570-word Academic Word List (AWL, Coxhead 2001) available

on the site.

One

disadvantage of using FE—which ironically is perhaps the main advantage of its

low-tech counterpart—is its lack of portability and accessibility. Many

students may not have access to Internet at home, and may not have sufficient

daily chunks of time to use the system at school. However,:this disadvantage

can be overcome by shrewd combination with other downloadable online resources.

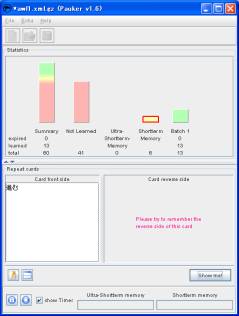

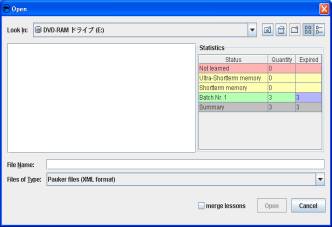

Pauker

(http://sourceforge.net/projects/pauker/) is a freeware downloadable Java

application into which FE files can be directly imported. It uses Unicode and

thereby avoids special character issues common on other sites. A set of cards

is reviewed in approximately 15 minutes, with each card passing through

ultra-short term memory (18 seconds), short-term memory (12 minutes) and a

final general review. When Internet access is impossible, this freeware provides

a viable offline alternative for reading files. However, due to the timed

nature of the program, it is not suitable for practicing writing files.

Figure 2.Pauker Screenshots

Although

Pauker can be used by students who have computers at home but no Internet

access, this still does not help those students who do not have computers

available. A cell phone version of Pauker has recently become available, but

whether it is compatible with any or all of the Japanese cellphone platforms

has not yet been determined. Other cellphone and PDA based flashcard software

is also easily found on the Net, but again compatibility both with Japanese

language and Japanese celllphones may prove to be problematic. This is a

subject for further study.

Another

previously discussed disadvantage of flashcards is that of lack of context.

When using FE to study established vocabulary lists such as the GSL and AWL,

however, supplementary online materials that allow a greater range of study

choices are relatively easy to find. With respect to the AWL, especially, the

following sites offer some excellent self-study supplementary material:

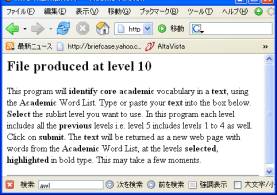

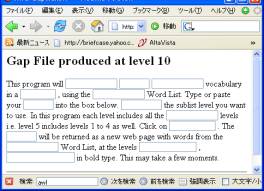

(1)

The AWL Highlighter and Gapmaker at

Nottingham University. On the Academic Vocabulary site at Nottingham University

http://www.nottingham.ac.uk/%7Ealzsh3/acvocab/index.htm , the AWL highlighter

can be used to produce text with the AWL vocabulary highlighted. This allows

students to produce their own readings in which they can review the vocabulary

they have studied in context. The Gapmaker on the same site can be used to

produce similar cloze style exercises for testing and reviewing the vocabulary.

Figure 3.

Results screenshots of the AWL highlighter (left) and Gapmaker (right)

(2)

Activities for ESL Students (http://a4esl.org/) a project of the Internet TESL

Journal (http://iteslj.org/) with

contributions by teachers around Japan and the world. It boasts a series of multiple

choice quizzes for both the GSL and AWL contributed by Kelly Quinn. Figure 4

shows a screenshot of one such quiz.

Figure 4.

Multiple choice quiz for AWL from Activities for ESL Students (http://a4esl.org/ )

(3) Vocabulary Exercises for the Academic Word List (http://web.uvic.ca/~gluton/awl/ ) is

part of the Gerry’s Vocabulary Teacher site. There are several Hot-Potatoes

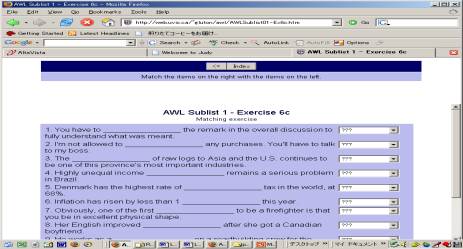

style matching exercises here for practice with the AWL.

Figure 5.Matching

quiz for AWL from Gerry’s Vocabulary Teacher (http://web.uvic.ca/~gluton/awl/ )

5. Conclusion and Directions

for Further Research

The present study describes a

variation of the Leitner method (the JY method) and documents a self-conducted

experiment by the author using this method to study Korean vocabulary on

Flashcard Exchange. It also describes how a similar method can be used with ESL

students to study the General Service List and Academic Word List, and presents

several complementary sites freely available.

This

method enhances the original flashcard benefits of effectiveness of learning

and retention by providing a review schedule that is intuitive and easy to

follow, as well as requiring production of vocabulary in writing. Moving the

system online and availing oneself of ready-made cards removes the tedious

requirement of having to create or input cards.

The

biggest drawback to using flashcards online is the lack of portability, one of

the greatest benefits of the paper version of the method. However, several

sites and software programs are available for cell phones (although they may

not be compatible with those in Japan) as well as PDAs. A stand-alone flashcard

drill system is also on the market in Japan, but unfortunately cannot import

the ready-made cards from FE. Even so, portability of the JY method should be

possible in the near future with appropriate software.

Aside

from portability, another difficulty in implementation would be how to make a

program such as this available to motivated students. The best solution would

be to structure an elective vocabulary course around it, which would require

daily effort from all registered students. Another would be to offer a

semi-self-study website linking all of these materials, but it is doubtful as

to how much the site would actually be used. In today’s world, where

opportunities abound at every corner of the Internet and “ESL vocabulary study”

produces 16,500 results on Google, students cannot be expected to choose from

the smorgasbord of study tools available what will actually work best for them.

6. References

Coxhead, Averil (2001) The Academic Word

List <http://www.vuw.ac.nz/lals/research/awl>

“Learning Theory - How MemoryLifter Works as a

Memorization Tool” (2004) on Memory Lifter Website

<http://www.memorylifter.com/learning/flash-cards.html>

Leitner, Sebastian (1972) So Lernt Man Lernen

(in German)., Germany: Herder Verlag

“Leitner Cardfile System” on Flashcard Exchange

Website, 2005 Tuolumne Technology Group, Inc

<http://www.flashcardexchange.com/docs/leitner>

Micheloud, Francois, ed. (2006) Flashcard Forum

on How-to-learn-any-language.com

<http://how-to-learn-any-language.com/forum/keyword.asp?kw=87>

Saruwatari, Asuka, Yoshihara, Shota and Suzuki,

Chizuko (2006) “Development of a Computer Assisted Flashcard System”, LET Kyushu-Okinawa Bulletin No 6 p.

13-22.

Schaefer, Jorgen (1997) “So Lernt Man Lernen”

(Book Review, In German), <http://www.forcix.cx/books/leitner72.html>

“System, Apparatus and Method for Maximizing

Effectiveness and Efficiency of Learning, Retaining and Retrieving Knowledge

and Skills” WO/2001/050439 Patent description,

<http://www.wipo.int/pctdb/en/wo.jsp?IA=US2000035381&DISPLAY=DESC>